Memphis to Little Rock took about 3 hours. We knew we wanted to see The Clinton Presidential

Library and The Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site. We decided to go to the High School site

first, hopeful that we could get in on a tour which happens only twice a

day. We just missed the first one, but

grabbed a spot on the 1:00 one, and so settled in to see what there was to learn

here. The high school is still an active school so the access is limited. The National Park Service site was across the

street. As it turned out, there was

plenty to see there!

A little review: In

1954, The Supreme Court ruled that separate but equal didn’t cut it in terms of

education, and ordered schools to integrate but with no timetable. (Look at our

blog Day 5, June 22nd for more

information about Brown v Board of Education). Not much happened in many states

after the decision. They tried to ignore

the Court. In 1955, the Supreme Court

ordered for a second time that the integration had to happen, now adding that

it should be done “with all deliberate speed.”

In 1955, in response to this

order, the school board and superintendent in Little Rock adopted a plan to gradually

comply, starting in the Fall of 1957.

They set highly restrictive conditions for admission to the premier high

school in Arkansas. These requirements

included both high grades and perfect attendance. The Black students would not be allowed to

participate in any extracurricular activities, including arts and sports. The

Board asked for volunteers and got 200 students who applied, but only 19 were

deemed to have met the high standards. As

it came closer to the time for school to start, death threats came to the

students and their parents. By the first

day of school only 10 black students were prepared to start. On that first day the students were told to

not come because of a huge mob outside the school.

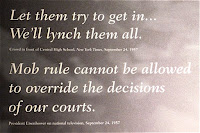

The second day, the Arkansas Governor Faubus intervened, but

rather than supporting the integration, he supported the segregationist mob and

ordered the National Guard to prevent the students from entering the

school. Nine of the students got the

message to travel together but one student, Elizabeth Eckford, arrived at the

school alone. After being refused entrance

to a door at the end of the building, she walked the full block in front of the

school to a bus stop where she hoped to escape the screaming, spitting

mob. One student followed her the whole

block, screaming vicious, despicable things the whole way. She eventually did

use a city bus to escape. The other nine

students arrived a short while later and were also turned away. The situation

was so ugly that one of the other students decided to give up, then there were

nine. For nearly two weeks, no further

efforts to enter the school were tried while the Nine and their parents wait to

see what will happen next. President

Eisenhower tried to convince Governor Faubus to comply with the court order.

A federal judge ordered the National Guard

removed and they turned over the situation to the Little Rock Police, who have had

little training in dealing with mobs.

The Nine return to the school where there is a large angry mob

waiting. The police slip the students

into the school where they go to their classes.

They were of different ages so they would be in classes alone or with

only one other member of the Nine. Many of the white students left the

classrooms when the Black students entered.

By noon, the mob was pressuring the police line, trying to enter the

school. At one point, one of the mob

said, “Just give us one to lynch.” The

police decided to evacuate the Nine, which they did safely. During all of this,

the press was very present and very ugly images went out into the world. When the mob realized the students were gone,

they turned on the reporters, especially the Black ones. That evening,

President Eisenhower had had enough and ordered in 1200 Federal Troops of the

101st Airborne, minus their Black members, plus placed the Arkansas

National Guard under federal control.

The troops rolled into Little Rock the next day. These were

trained soldiers, most just having returned from the Korean War, whose mission

it was to get those students in and attending school. We heard reports of the General calling a

school assembly and letting everyone know no trouble would be tolerated. Many white students transferred to private

schools and other school districts. The Nine

were at last allowed to go to school, but did so under armed guard every day.

They were in school but, for them, the

situation moved into shunning and harassment on a daily basis: everywhere they

went from gym class to the cafeteria to the hallways and sometimes during class

itself. Some teachers were very

supportive of the Nine, and other teachers turned a bind eye.

The National Park Service had many first person interviews and news clips from the

time, so that we felt like we could really gain an understanding about what this

was like. One of these high school girls,

Melba Pattillo, wrote, “Each day I polished my saddle shoes and went to war.” It seemed like that was a good description.

When they finally got through that year (school year 57-58)

and the one Senior of the Nine, Ernest Green graduated. The Governor and

school board tried a new tactic. As long

as they were being forced to integrate, they would totally close down all the

public high schools in town. And they

did for the whole next year, known as "The Lost Year.” There was a long community battle for power

which eventually ended in removing from the school board the segregationist

members and reopening the schools the next year.

After spending this time in the National Historic Site Visitor's Center, we then had the chance to go into

the school on our ranger tour. Having

had so much background about the racial struggles there and elsewhere during

this period, it was extremely moving to go visit this school. It is still a very nice school. On this summer

day, they were doing registration and photos for the Fall. It is still very much a public school, but

entirely integrated.

As we entered the front door of the school, we immediately

saw the extensive display of the story of what happened here in the late 50s. The

display honored those 9 students, The Little Rock 9, who so bravely took on the

challenge of breaking down that educational barrier. There were photos of the each

of them, both at that time and more recently. Several of the Nine had written books about their experience. The books were

on display there, too. All incoming

freshman were required to read one of them to give them a sense of the important

history of their school

As we were brought through the

auditorium, the cafeteria, the hallways, we saw young people and parents and

school staff of a variety of different ethnic and racial backgrounds. We know that the school district was not

finally fully integrated until 1972, but we could see that this school, that had

been in the center of such a storm, had eventually come out of it in the way it

should have been. It was good to see this group of students on the stage, knowing that none of the Nine would have been able to join in such an activity.

Across the street from the school was a moving memorial with

photos of important happenings through the past 60 years at Central High School. One of the photos that struck both of us was

the one of Elizabeth Eckford and the former student who had been so terrible to

her on that day in 1957. An apology was

offered and accepted. We felt this was a

symbol of the reconciliation that has taken place in the community.

We left this highly intense National Historic Site

experience filled with awe at the courage of these young people to face the

hate everyday throughout their time at Central High School. In the midst of death threats and constant

insults and harassment, they sought and achieved the education they were

desired. Some became adults who stayed

quietly in the background, they appeared to have had their time of front-row

action. Others continued to be leaders

in gaining equal treatment. We have a

deep appreciation and respect for each of them.

We then drove by the Arkansas Capitol

Building and on for a couple more miles to The William Jefferson Clinton Presidential

Library and Museum. This is our 5th

and last Presidential Library of this trip.

We are becoming more familiar with how these places work, and were able

to soak in a lot of information about the Clinton White house years as well as

some of his life before Washington.

They did a very complete job in terms of talking about his accomplishments

during that period, a time of amazing prosperity for the country. They were quite light on some of the self-inflected

problems of the Clinton Presidency.

Monica Lewinsky’s name was mentioned once. The whole impeachment effort

was blamed on his political opponents trying to take him down rather than any

discussion about how he had contributed to it.

Bill Clinton was 10 years old

when the crisis at Little Rock Central High School took place. Living in Arkansas, his home was filled with discussions about what

was going on in Little Rock. This was an

event that had a big impact on the young boy.

As President, he supported the Congress to awarding each of the Little Rock

Nine the Congressional Gold Medal. This and the Presidential Medal of Freedom

are the highest civilian awards in the country.

One of the medals, collectively given to the Library by the Little Rock

Nine, is on display along with photos of the ceremony during which they all

received their medals.

That said, there were also lighter subjects

to view. We enjoyed seeing a table set

for a White House dinner, gifts of saxophones, lot of other interesting

artifacts, and seeing what the cabinet room looked like.

We had a very interesting talk with Claudette, a volunteer

docent, and D. Belcher, a security guard.

Each had been involved with the Clintons and the Library for quite some

time. This conversation was the

highlight of the visit to the Library.

We talked with them about the Clintons, current politics, times when

each of them had met Bill, and many other interesting things.

Just outside of the Library we found one of the Anne Frank

Chestnut trees. There are nine saplings,

from the tree Anne Frank could see from her sanctuary and wrote about in her

diary, that have been planted in the United States. Having been to the Anne Frank House in

Amsterdam in 2014, it was heartening to see this symbol of her spirit.

Then it was hop in the very hot car to drive to Hot Springs

AR ... and to grab some quick dinner at the Indian restaurant that was in our

hotel building. Nice to not have to go

far for dinner…the evening was not inviting!

Hot, hot, hot! Well over 100. And

humid!

No comments:

Post a Comment